By Jane Hatfield

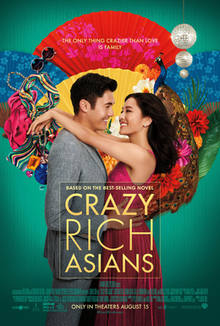

Although attempting to be progressive as the first Hollywood film with an all Asian cast in over 25 years, Crazy Rich Asians perpetuates traditional gender norms of hegemonic masculinity and femininity. The texts Everyday Women and Gender Studies and Gender Inequality help display the implications of the movie’s differing portrayal of both genders.

The bachelor and bachelorette party scenes in the film define typical gender roles as the men party, drink, and shoot guns while the women shop, gossip, and tan on the beach. At the bachelor party, the men are constantly surrounded by beautiful female models, all of whom sit around them or on their laps in tiny bikinis. This portrayal of women reinforces the belief that women exist only in order to appeal to men, to be seen as sexual, beautiful objects for the taking. As Judith Lorber explains in Gender Inequality, “one of the manifestations of men’s objectification of women is the male gaze, the cultural creation of women as the objects of men’s sexual fantasies” (174). The scene further supports traditional masculinity when one bachelor takes a bazooka gun and fires it off of the ship. Since this act of aggression and the use of guns is seen as stereotypically male, Crazy Rich Asians supports traditional gender norms. In “Racializing the Glass Escalator,” Adia Wingfield concludes, “contemporary hegemonic masculine ideals emphasize toughness, strength, aggressiveness, heterosexuality, and a clear sense of femininity as different from and subordinate to masculinity” (266). Through its bachelor party scene, Crazy Rich Asians perpetuates hegemonic qualities of masculinity and depictions of women as subordinate to men.

On the flip side, the Asian women in the bachelorette party spend most of their time on a shopping spree, squealing with joy at the thought of buying new clothes and products. The portrayal of characters Araminta, Amanda, and Francesca as product-crazy consumerists redefines the stereotype that femininity is defined by an interest and dedication to beauty. In “The Muslim Women,” Lila Abu-Luhgod states that America is “a nation that exploits women like consumer products or advertising tools, calling upon customers to purchase them” (31). While reinforcing the idea that women are the primary consumer of beauty products, the film also suggests that women themselves are a product to be consumed, as evident in the sexualization and objectification in Crazy Rich Asians’ bachelor party scene. Further, when Amanda and some of the other girls leave a dead fish on Rachel’s bed with the words “gold-digging bitch” written on the mirror, Crazy Rich Asians perpetuates the stereotype that women are inherently bitchy and love to gossip, especially when it comes to their boyfriends.

Overall, whether overt or not, the differing portrayal of females and males in Crazy Rich Asians reinforces hegemonic masculinity, As Braithwaite and Orr state in Everyday Women and Gender Studies, “these are the characteristics of real men constantly re-presented around us, in everything from popular culture (film, TV, music videos) to the workplace; indeed there is a long history of such representations of what has been called hegemonic masculinity” (311). Since the film constantly switches back between shots from the bachelor and bachelorette parties, Crazy Rich Asians helps to contrast and define what it means to be feminine and masculine.

Note: This essay was written by a student in Dr. Heidi R. Lewis’ First-Year Experience (FYE) course FG110 Introduction to Feminist and Gender Studies. FG110 teaches students how to examine, power, inequality, and privilege along the lines of gender, sexuality, race, socioeconomic status, age, physicality, and other social, cultural, and political markers using multi-, inter-, and transdisciplinary approaches. The students visited a local theatre to screen Crazy Rich Asians, and this essay was written in response.