By Christopher Curcio (Staff)

Growing up in the seventies, the boys department at Sears was, to me, about the dullest and most depressing place in God’s creation. So I guess it’s only fitting that amidst that foreboding landscape of black, brown, grey and navy blue I learned one of the hardest lessons of my so-called boyhood—being a boy sucks.

Growing up in the seventies, the boys department at Sears was, to me, about the dullest and most depressing place in God’s creation. So I guess it’s only fitting that amidst that foreboding landscape of black, brown, grey and navy blue I learned one of the hardest lessons of my so-called boyhood—being a boy sucks.

My first memory of that dark, dismal back-alley where color goes to die is from my summer before the second grade.

The year was 1971. Dad was called away to do a second tour of Vietnam and for some reason Mom and the rest of us relocated from western Maryland to the sunny eastern coast of Florida.

Totally ignorant of the enormity of my father’s situation (it never once occurred to me that he might not come back), I was excited and thrilled at the prospect of moving to a place where the sun shone year round and the beach was a mere 10 minutes away!

A few weeks before school started, my mother decided to take us on a back-to-school shopping trip. I had never been clothes shopping before and was thrilled about the idea of wearing shorts all year long! Well, that excitement was short lived when I got a glimpse at the limited choices available to me. “Is this it?” I remember thinking. “Is this all there is?”

Shocked and numbed by the plainness of the selection (2 styles of shirts—pullover or button down; 2 styles of pants—short or long) and that almost complete lack of color, I finished my shopping in about 15 minutes. My only treasure was a pair of red, white and blue sandals with stars on them left over from a Fourth of July display.

Looking back, I really can’t say what I was hoping to find. The colors and styles of the clothes on the racks were pretty much the same as the ones I was wearing. But for some reason, I was expecting more—a lot more.

Now, if the boys department could be compared to the sepia-toned bleakness of the Kansas prairie, entering the girls department with my Mom and sisters for the first time was like dropping 10 tabs of the best acid and being blasted into Oz.

A galaxy unto itself, the girls department boasted every color in every shade and hue known to mankind (and a few Mother Nature never intended). Purples, oranges, yellows, pinks, greens and blues brighter than the sky smiled at me from every corner. Dresses, blouses, skirts, shorts, hats, sunglasses, necklaces, bracelets, shoes (and even socks!) in every style and color imaginable hung from every rack. Over the rainbow? Honey, I was inside the rainbow and had absolutely no desire to go back. Fuck Kansas.

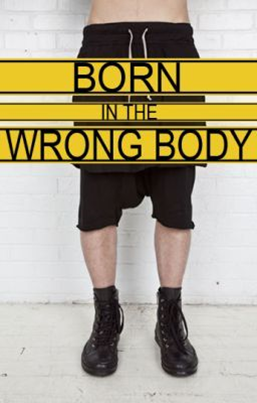

And so it was, in the middle of that glossy, sparkling, glitter-and-sequined universe, that the faintest glimmering of an idea started to take form that would eventually blossom into the most important lesson of my American childhood: somehow, I don’t know how, I had ended up in the wrong body.

Of course, as a pint-sized 6 year-old, I didn’t have the words to articulate this. All I knew was that as I grew, something wasn’t quite right. Sure, when I looked at my body I was definitely a boy, but everything my heart wanted and desired screamed “Girlfriend!” Easy Bake Ovens, LiteBrites, tassels on my handlebars, bell-bottom flares, Sun-In and Bonne Bell Lipsmackers—all denied me simply because I wasn’t born with a vagina. So, with my head down and my mouth securely shut, I allowed society to create my sterile, colorless existence as a “boy”.

A little over a decade later, the moment I realized my ever growing attraction to men was not a passing phase, I started to self-identify as gay. And in the eighties, there weren’t that many labels to choose from: if you were a guy who liked guys, you were gay; if you were a girl who liked girls, you were lesbian. If you liked both you were…well, a slut.

However, knowing what we know now about the amorphous nature of gender, I wonder if it would be more accurate to start identifying myself as transgendered.

I mean, even now, rapidly approaching 50, I can honestly say that there has never been a single moment in my life when I have ever identified with the gender assigned to my sex. For example, as a boy, I avoided other boys like the plague. Their rough and tumble nature frightened me so much that I hung out with the girls, people with whom I actually had something in common.

And except for a brief stint in Little League Baseball—an exercise in humiliation I vowed never to repeat—everything I was expected to love as a boy (sports, camping, and anything remotely involving physical prowess) I found intimidating and impossibly dull. And everything that was considered girly (jumping rope, hopscotch and just about anything involving yarn) attracted me like bees to honey.

As a “man,” I look at the aggressive, macho, one-up behavior of my fellow bunkmates and say “WTF?” I just can’t, and probably never will, relate. Except for sharing the same genitalia and clothes, the similarities are pretty much non-existent.

For decades I’ve joked to my friends and referred to myself as a woman trapped in a man’s body. But maybe it’s not a joke after all. Perhaps, for whatever reason, it’s the God’s honest truth. And while I have no plans to surgically alter my body, I do have plans to reincarnate. And I’m hoping next time Mother Nature will get it right.